Introduction

The previous sections present the lessons Center staff learned from their experiences working with Tribal communities and organizations to develop, sustain, and evaluate their child welfare programs. These pieces include stories about these experiences as well as some high-level generalities drawn from them.

This section provides examples of tools that the Center used in its work with these programs. Part of the Center’s journey has involved developing evaluation strategies and tools that:

Honor local knowledge-making practices;

Elicit accurate and meaningful information about the program and its impact on participants and the community; and

Avoid the pitfalls that Western-style evaluation strategies and tools often fall into when working in Indigenous communities.

The selections here cover the lifecycle of evaluation work, from getting a sense of who people are and what they want to know about the program (and its desired effects) to gathering information from participants to putting the gathered information together in a way that tells a meaningful story about the program’s effect on the community.

You will notice new terms in this discussion, such as “Mind Mapping” and “meaning making.” These terms refer to processes adopted by the Center to make evaluation activities more culturally responsive, effective, and respectful while avoiding terms potentially laden with historical trauma due to their association with intrusive research methodologies. Adjusting our vocabulary opened the doors to new ways of doing this work informed by the principles of Indigenous Way of Knowing. (For more information on Meaning Making, Mind Mapping, and related terms, proceed to the final Lessons Learned section: Terms of Art.)

Mind Mapping

The implementation and evaluation processes that we used included an evaluability and a community readiness assessment. Another component of these processes was establishing the community’s vision for the program and identifying its outcomes of interest. The Aleut Community of St. Paul Island Tribal Council established the Txin Kaangux Initiative (TKI) to integrate services and bring a holistic approach to healing and wholeness that relies on collaboration and creativity in service provision.

One of the critical pieces of our work with TKI was a creative group activity called Mind Mapping. In essence, Mind Mapping involves creating a visual representation that brings out implicit ideas that might not have been captured by more literal and linear discussion. We used Mind Mapping in a variety of ways; in some cases, it acted as a sort of Indigenous logic model (especially in conjunction with the Pathway to Change) and primed discussions about research questions, crystalized cultural metaphors to guide the evaluation design, and identified outcomes of interest and core cultural values.

For purposes of the Center’s work with TKI, the Mind Mapping exercise helped identify the community’s outcomes of interest for the evaluation period. Because one of the Initiative’s leaders had previously mentioned the importance of artistic expression to their team, we knew that Mind Mapping would align with the values of this group while supporting the goal of establishing a shared vision for the Txin Kaangux Initiative to inform the priorities of the evaluation.

We facilitated TKI’s use of Mind Mapping to understand the community’s outcomes of interest through these high-level steps:

-

Seeding the conversation

by asking the participants to create their own visual representation by

reacting to one of two prompts:

- What is the primary change that will occur within families or the island community of St. Paul once the Initiative has been running for a while?

- How will knowing, understanding, and embracing sovereignty and self-responsibility impact the community?

- Hosting a discussion of the resulting representations, allowing the members of the group to explain their work and how it addressed the seed prompts.

- Helping the participants identify the themes they want to incorporate into the single vision embodied by the Mind Map as well as the representational elements that would be key for doing so.

- Creating an initial representation to begin the iterative process that would make explicit what had been embedded in the representation.

- Having participants identify “activation words” (the words that come to mind when looking at the picture), starting with as long a list of activation words as the TKI team came up with and then narrowing them to a consensus on eight main concepts.

- Specifying the activation words using short phrases that identify how the team would know that the Initiative had been successful in each of the areas identified by the “activation words.”

At the end of the process, we worked to develop a graphic of the Mind Map as a gift to the community.

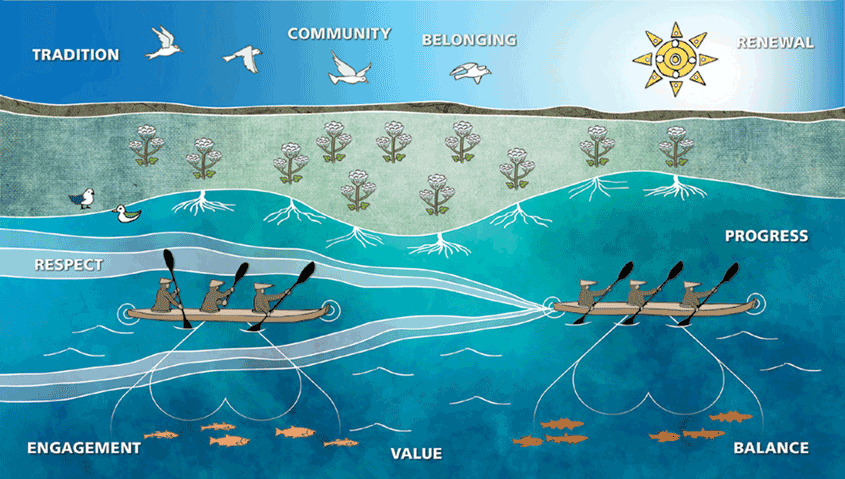

TKI Sea of Change Mind Map

The individuals paddling in the Baidarka, or Unangan watercraft, demonstrate the importance of working together. When paddlers do not paddle in unison, as shown by the left Baidarka, the journey is more strenuous and frustrating. However, when the struggling paddler has someone modeling ahead of them and someone supporting them from behind, the community moves to the second Baidarka, as shown on the right, with everyone paddling together. The wake of the latter Baidarka serves as a guide for those behind it, leading the way.

The sun symbolizes what the paddlers are traveling toward: light, warmth, energy, love, and life. The poochkis (the plants on the shore) and their roots symbolize the culture, traditions, history, and way of life for people on the island. What is beneath the surface is responsible for all that blooms and flourishes on the bountiful island. This is also represented in the reflections of the hearts that are beneath the paddlers, to remind the community that the love and spirit that guides our work, even if not always visible, is always there.

Word Cloud Personal Reflection Tool

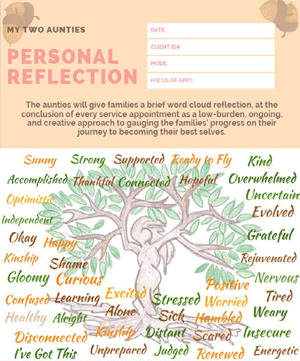

Finding information gathering tools that invite candid and useful responses from people using child welfare services can be an ongoing challenge. Part of the work we did with the My Two Aunties (M2A) program, housed in the Tribal Family Services (TFS) department at the Indian Health Council (IHC) located on the traditional homelands of the Payómkawichum, or Rincon Band of Luiseño Indians, involved helping M2A develop a culturally grounded tool for gathering information about how mothers felt after engaging with M2A services.

The concept for the tool originated when the Program Director expressed interest in a tool understanding how clients experienced their visits with the Auntie and how they felt after each visit—as well as to track healing and growth over time. At first, we inventoried existing Likert or rating scales and other assessments that the Aunties could use at the end of family visits to score family responses along a range of experiences. However, these ultimately did not align with evaluation goals and were not normed or tested with Indigenous people. The instruments also felt too far removed from IWOK and the oral tradition. Additionally, the Aunties and Program Director expressed concern that quantitative tools might threaten the therapeutic rapport with families.

We worked with the M2A program to leverage some positive feedback about mothers being able to choose a word or feeling that captured their visit with the Aunties. The Program Director liked the idea of including a culturally relevant visual to engage the families in something vibrant and eye catching. After much trial and error and consultation with the M2A team and IWOK consultant, the Center team finished the design of the tool, which presents a meaningful image and an array of expressive words that cover a spectrum of positive, neutral, and negative feelings. The image is of the mother oak, which is a powerful representation of local IWOK. The words are presented randomly around the culturally meaningful image of an oak tree. The words included were chosen by members of the M2A team. At the conclusion of each service appointment, the Aunties spent about 3–5 minutes administering the tool. Mothers were asked to circle up to five words and were given the option of writing in responses if the words they are feeling were not represented in the word cloud. Clients could engage virtually using an online version of the tool.

The result is a low burden, culturally grounded approach to informing continuous quality program improvement. However, it was useful for even more; after fielding the tool, the M2A project recognized the tool’s potential for helping Aunties connect mothers to additional services or referrals based on responses. The tool helped the Aunties to better understand client needs and offer inroads into probing for and providing other supports or referrals to additional services based on their responses, better tailoring their services for mothers and improving the quality of their visits. To that end, the Aunties created a Word Cloud Personal Reflection Tool tracker, where they entered client responses alongside clinical notes, which helped them assess healing over time and further respond to emergent client needs.

Personal Reflection Toolkit

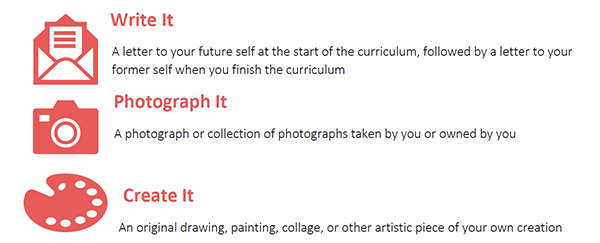

A similar set of challenges arose in our work with the Tlingit and Haida Tribal Family and Youth Services Department (TFYS) on its Yéil Koowú Shaawát (Raven Tail Woman) curriculum. After some trial and error, partnership from the group facilitator, and leadership from an IWOK expert, we ultimately co-developed a personal reflection toolkit to support the evaluation, better understand how the Yéil Koowú Shaawát (YKS) curriculum impacts the lives of women and their families, and better understand the healing journey along with the hopes, fears, and dreams of the participants. The toolkit provided women with options to share their stories in one of three formats at entry and exit from the program: photos, letters to future and former selves, or artwork.

The toolkit was designed to have personal reflection activities at the beginning of their participation and then again at the end, reflecting on hopes and personal goals at the time of entry and upon graduation at the completion of the curriculum. The women each chose how they wanted to create and share their personal reflections from one of three formats: letters to themself, photographs, or visual narratives. Following the completion of their reflection, meaning making interviews were facilitated jointly by the facilitator and Center team member. The interview focused on understanding their personal reflection and how it represented their personal change through the healing journey.

A graphic from the handout showing three suggested formats for sharing personal reflections.

Women felt empowered to tell their story in a manner that connected for them, whether through art or writing, and being able to choose how to share is especially important for trauma survivors, whose previous experiences are often associated with a lack of control or choices. These methods provided insight into women’s developing resilience, particularly around decision-making skills, nonviolent communication skills, respect for self and others, stress-management strategies, and planning for and taking steps to realize a positive future.

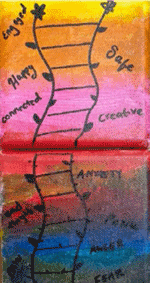

For example, one woman chose to illustrate her healing journey by creating an original painting at entry into the women’s group and again after graduating. Her first painting depicts two canvases, one that is primarily dark tones and another that has vibrant lively tones. She described the yellow tones as idyllic happiness and the dark tones as mercurial and depressive. When asked to describe her painting and what it depicts or means to her, she said:

So yeah, I think yellow I kind of associate with just kind of warmth and happiness because I think when you see, you know, smiley faces they’re usually that bright yellow. And then, you know, in Alaska too, when the sun comes out, it’s just kind of gorgeous and everything. And so I just kind of think of yellow as just a happy color in general. And so, yeah, when you said, “Think about who you want to be, what you project yourself,” yellow was the first color that I thought of. And so that was the first color I chose when I did that painting. And then I was thinking, “I’m not there yet—I’m not yellow—I’m not happy. What kind of step-by-steps am I going to have to do to get there?” So that’s when that yellow kind of blended into that orange, which kind of blended into that red—to show the different layers.

She later revised the painting, adding additional content that helped describe her insights into her journey and provided a source of guidance as she dealt with the challenges of healing:

You know, I think since group ended, there’s been a couple days where I just I’ve had to be immobile for maybe an hour or two, or maybe the entire afternoon, and just lay down because I get so overwhelmed. But I saw this picture of the ladder in my head, just knowing that, okay, I’m going to be able to get back. I need to take this time and just recognize how I’m feeling before I can get back to that place where I am feeling safe, and happy, and connected, creative, engaged.

Healing Village

In assembling the information gathered to understand the program’s effects on the community, it can be helpful to engage the community, having them review the gathered materials and offering additional meaning and context to them. When working with TFYS on YKS, we discussed several engagement options that ranged in degrees of community ownership, engagement, and depth of participation. It became clear that the Center’s deep community engagement should be maintained through the analysis and reporting period, so we worked with the program and the community to convene an advisory group, which chose the name “Healing Village” for itself, comprising recent graduates and current participants of the women’s group, the facilitator, co-facilitator, and a local Tlingit Elder during the final phase of the evaluation.

In the short term, as the Center team prepared information for analysis and conducted an initial thematic analysis of information sources, the Healing Village’s role would be to:

Ensure accuracy of initial evaluation findings (Did we get the story right?)

Prioritize findings (What elements of the story should we highlight or emphasize?)

Add depth, context, and nuance to findings (Where should we dig deeper?)

Address unanswered questions and clarify interpretation of findings (Is this cultural concept or experience accurate?)

Identify emergent themes or gaps in our analysis (What do you see and what is missing?)

Based on feedback we received, the Center team prioritized initial findings the Healing Village identified as important, incorporated themes emerging from the meetings, and adjusted and reframed initial findings to ensure accuracy. After several weeks of additional review and collaboration, the project team solidified a set of cross-cutting findings derived from evaluation information sources and input from the Healing Village meetings.

The long-term role of the Healing Village was to share stories of healing and strengthened cultural resilience in the broader community and Indian Country at large. In addition, the Healing Village’s involvement served as a vehicle for ensuring the fidelity and integrity of the curriculum as implemented, while educating community leadership to carry the message and lessons of women’s experiences forward to benefit others and future generations.

The group member who produced the paintings, above, shared how the work of the Healing Village in learning about her experiences with the women’s group felt congruent with the Talking Circles conducted by the group itself.

I guess for me I can understand it because I’ve done evaluations of programs and things before, so I know when you’re doing that process that you really need honest feedback in order to really get a whole picture. And so it’s unusual to be on the other side of that. So I appreciate how holistic this approach has been because it doesn’t feel any different than any of the other Talking Circles—it really just feels like an extension of it.